2 What Is Life?

Baby don’t hurt me, don’t hur-ahem, excuse me, yes, let’s get back to biological science here. To really seriously understand the living environment, we need a picture of what Life is.

One way to build this picture is to try to look at many living entities and compare them to a random bundle of non-living entities to see what really differentiates them. Let’s consider a pretty obvious example, a rock versus a squirrel that might pick up and examine that rock, for example.

We might say that the squirrel is different from the rock because no matter what temperature it is outside, the squirrel stays the same temperature. That is, it maintains homeostasis. Homeostasis is the state of having steady levels of certain chemical or physical quantities. For example, temperature is a physical quantity, and the squirrel maintains its temperature within a narrow band. Pushing the temperature back into this band when the squirrel is in a cold or hotter place is called dynamic equilibrium.

The rock, on the other hand, becomes colder in the winter months, as opposed to the summer.

Just maintaining temperature isn’t sufficient to define what entities are alive though. Think of an alligator. The alligator is cold-blooded or ectothermic. It adjusts its internal temperature to the outside environment, so when it’s just a little bit colder outside, the alligator will be in extremely serious danger.

Homeostasis is a balance of many things, the acidity in different microscopic environments in the body, the temperature, the amount of sodium per cubic inch, the materials making up the scales of an alligator, the electrical energy consumption of the brain, the “brain waves”, the rhythms of the heart, and so on.

A rock has no such balances. If water starts to drip onto a rock, it will slowly change form and a hole will form in it. When rain drops drip onto a human, an alligator, or a squirrel, the same erosion of chemicals takes place, but they are quickly replaced by the body.

This constant cycling of materials and replenishment is what distinguishes life. It requires energy, just like a car needs fuel and oil to keep running.

In fact, humans and other organisms are very similar to machines, which also keep chemicals and systems in balance. It is very hard to distinguish them, which is what has lead to a lot of science fiction about “cybernetic” organisms.

Just like a machine, the fuel (in our case food) is broken down utilizing oxygen to produce mechanical, chemical, and electrical energy in a process called respiration. The actual breaking down of chemicals is called catabolism and the coming together of chemicals into much larger ones, which the body also does, is called anabolism. These combinations of breaking down and building up are referred to as the body’s metabolism.

It turns out living things share even more things in common than just metabolism and homeostasis themselves. They engage in the following processes:

- transport: moving things around in the body, like food or oxygen molecules.

- nutrition: absorbing the energy from food and replenishing important machines in the body by breaking down food into its component chemicals.

- excretion: removing waste chemicals after the breakdown described above, as well as anything else that’s not supposed to be in the body.

- respiration: the actual chemical process that gets the energy from the final products of the food breakdown, using oxygen (aerobic respiration, which we do) or without oxygen (anaerobic respiration, which plants do).

- growth: The development of organisms either as they age or in response to a stimulus (a trigger).

- synthesis (anabolism): The development of larger storage molecules and other components from smaller, simpler chemicals.

- regulation: processes like dynamic equilibrium that control activities in the body, including feedback mechanisms.

Finally, perhaps most crucially, organisms can reproduce. The offspring are similar to the parents, for reasons we will discuss in a bit. No other non-living entity does the same thing, except perhaps viruses.

2.1 The Cell Theory

These processes are perceivable to anyone that studies organisms (biologists), so for thousands of years, these ideas were used to distinguish life. However, as we developed the compound microscope using a physics field called optics, we were able to look at life on the microscopic (micrometer length) scale.

We discovered there’s a whole ecosystem (collection of interlocking non-living and living systems) of organisms at this small level, including bacteria, archaea, diatoms and fungi. Not only this, but we realized there are these tiny compartments shaped a bit like spheres that all organisms share called cells. Here are pivotal moments in that timeline:

- Robert Hooke (1665): Coined the term “cell” after observing cork cells under a microscope.

- Anton van Leeuwenhoek (1674): First to observe living cells (bacteria and protozoa).

A few hundred years after study of tons of these cells by many scientists, Theodor Schwann and Martin Schleiden had a short conversation in 1838 in which they developed a scientific theory of cells. A scientific theory is a set of fundamental principles to explain some broad collection of events (phenomena) developed after observing the results of many experiments and finding patterns between them.

An English translation of the manuscript Schwann published after this meeting explaining the cell theory is below:

https://wellcomecollection.org/works/d8xb3m37/items?canvas=7

Most people summarize the cell theory as stating three things, but it is a much more extensive theory that actually describes the components of cells and how they behave.

The three aspects of it you should know are:

- All living things are made of 1 or more cells.

- Cells carry out all of an organisms life functions.

- All cells come from other cells.

You might wonder about the third principle here. If all cells come from other cells, where did the first cell come from, or is it just cells all the way down through history?

Not every proposition in a scientific theory needs to be true. This may be a shocking idea, as we’re taught to think that science is this infallible thing. However, sometimes, scientists are only interested in developing a “picture” or “model” of the real world. The model we described of clothes spending, for example, wasn’t “lliterally true”. It’s almost never the case that people spend exactly 3% of their income on clothes. The model just helps us predict and describe clothes spending phenomena to a certain accuracy.

Similarly, even if the first cell ever didn’t come from another cell, the cell theory explains where the vast majority of cells come from, so that makes it a very good theory.

Understanding organisms as big collections of very similar compartments is a very powerful idea. Schwann was actually the person that coined the word “metabolism” to describe all the chemical processes in a cell. It turns out the body is modular. It breaks up the process of respiration and other processes over many cells, so if one cell fails, or dies, many others can take over. This is part of why we are so good at maintaining homeostasis. The system is almost “failure proof” because we have billions of cells.

2.2 Organizing Life

The change in these collections of living cells (organisms) is described by one of the other most important theories in the history of biology, the theory of evolution through natural selection. We’ll explore this topic later. For now just know that organisms change over time because of changes in their central processing systems that are passed on to their offspring through reproduction. The central “control system” of the cell is its DNA, or its genome, more appropriately, which is made up of DNA, which is DeoxyriboNucleic Acid, a chemical compound.

We’ll begin our exploration of the wide diversity of organisms and ecosystems by zooming in on the components they all mostly have in common, their cells.

However before that, we need to try to categorize life in the most broad way possible. Scientists have tried to do this for centuries, but we’ve landed on a widely agreed upon top level of three domains of life. A domain is the most broad organizing category of life we use.

The three domains are:

Bacteria

Archaea: Similar organisms to bacteria, includes the extremophiles (organisms that can survive extreme conditions like acid and volcanic rock)

Eukaryotes (Eukaryota): includes all animals and similar organisms.

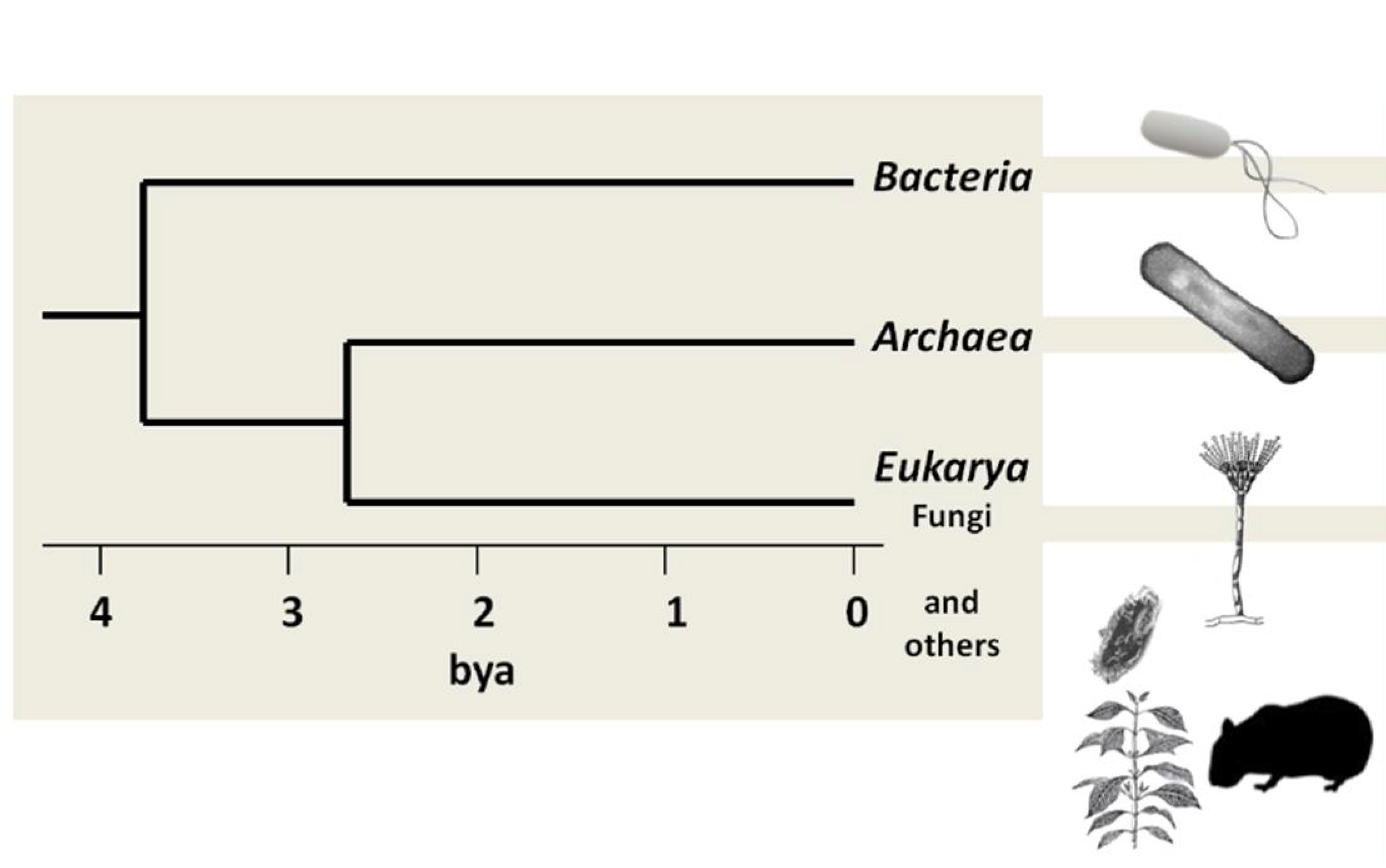

Here’s a picture that illustrates the organization of these categories

Note: The Bacteria and Archaea, because they are so similar, are often referred to collectively as Prokarya or the Prokaryotes, but remember that this is an informal grouping. They are fundamentally genetically different domains of life in our modern system of classification.

The timeline actually illustrates that this organization system is a family tree. Organizing the different categories of living things actually involves creating a geneology of them, because it turns out organisms share a lot of their DNA, their genetic material. We can think of them as related to each other, and this is what the theory of evolution proposes. The 5 numbers on this timeline each represent “billions of years ago” (bya). So about \(3.7\) billion years ago, the first cells split into two groups, the bacteria and another group, and that other group split off into two more groups about a billion years later, the archaea and the eukaryotes

If you want to get a head start on exploring phylogeny, the subfield of biological science that deals with family trees, check out this interactive zoomable tree of life:

Finally, it turns out the prokaryotes’ cells look a bit different from eukaryotes’ cells, which we’ll discuss more in depth in the next chapter.